Alexej Gorlatch, Pianist in Review

Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall

April 14, 2011

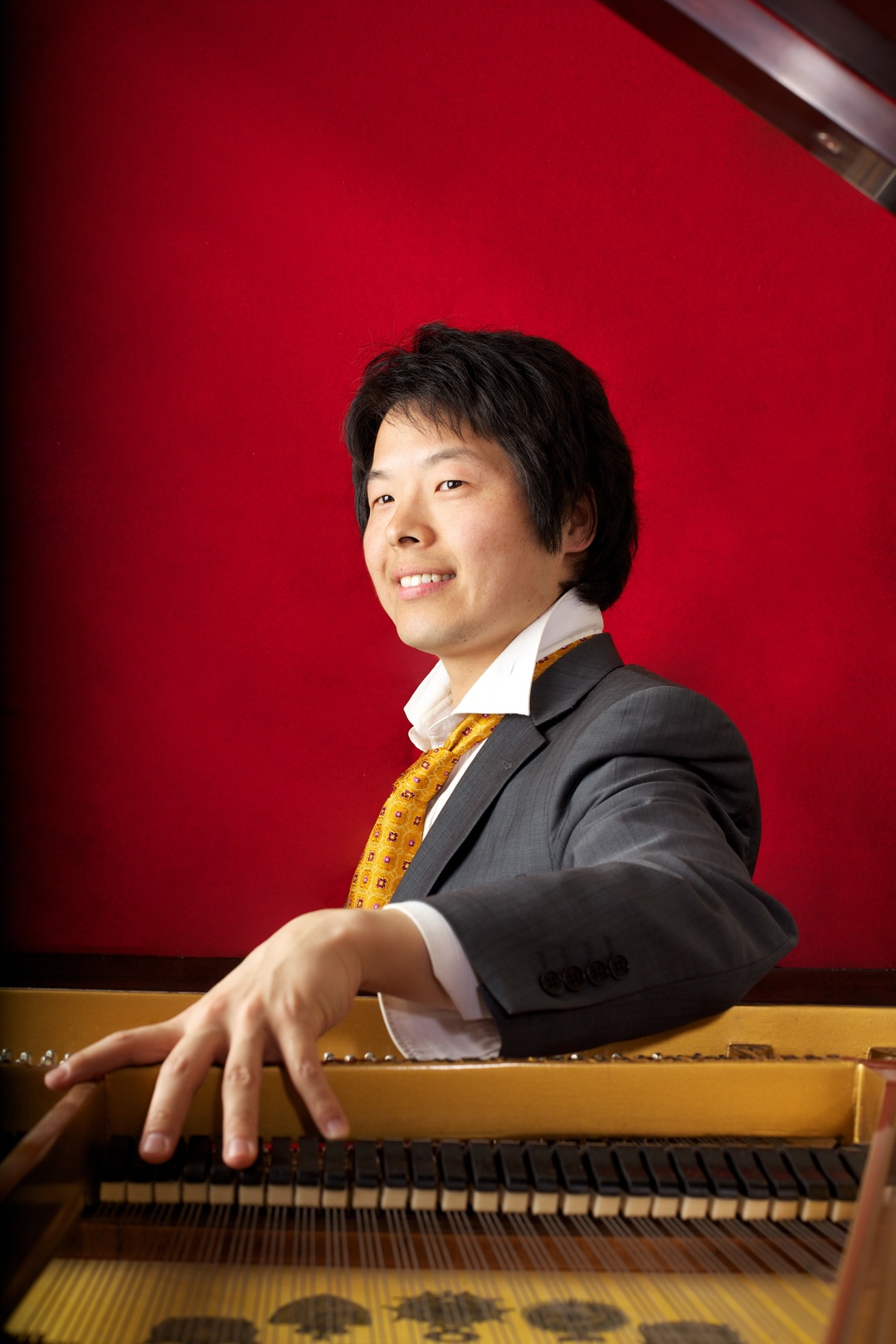

Alexej Gorlatch; Photo Credit: Akira Muto

Judy and Arthur Zankel Hall, part of the Carnegie Hall complex, presented Alexej Gorlatch on April 14th as the First Prize winner of the AXA Dublin International Piano Competition. Gorlatch, who is 22 (born in Kiev, in 1988), was also the Silver Medalist at the 2009 Leeds International in the U.K., where his performance of Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto elicited a glowing comment from the Guardian (Manchester): “…immaculate in its poetry and aggression.” Those two characteristics, when you think of them, are more apt than conflicting for that particular Beethoven masterpiece; certainly Gorlatch’s technically superb pianism at the Zankel recital was impressive for its “poetry” but, let’s face it: any hopeful who could enter–and triumph–at so many daunting marathons would, ipso facto, be an “aggressive” and determined, self-assured contender!

Mr. Gorlatch’s burgeoning career has been adorned by a succession of prizes and honors since he was eleven-years-old. To name some: the German National Jugend Musiziert Competition (several times); the Steinway Competitions of Berlin and Hamburg; the Grotien Steinweg in Braunachweig; and the Robert Schumann Competition for Young Pianists in Zwickau, where he was awarded the Yehudi Menuhin Prize for best participant. He garnered prizes at the Vladimir Horowitz International Competition in Kiev and at the Chopin International in Warsaw.

In fact, this writer covered the then 18-year-old artist’s April 4, 2007 recital at Weill Hall when he came to us as the winner of the 2006 Hamamatsu International Competition (reviewed in Volume 14, No. 3 of this magazine.) His program at the time included the Beethoven Sonata, Op. 101, Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces, Op. 12, and all twelve Chopin Etudes, Op. 10. I praised his Beethoven as “structurally clear, tautly organized and sensibly clarified…a young man’s approach…Though additional areas of experience and insight may undoubtedly reveal spiritual mysteries, Gorlatch’s way was certainly on the right track.” The Schumann tone poems were “thoroughly idiomatic: clearly and simply phrased and free from affetuoso point-making… His playing represented the best of the best of the admirable Teutonic tradition (Gorlatch has been living and studying in Germany), with warm, robust down-to-the-bottom-of-the-keys sonority, yet with sufficient glow and color and ardent rhythmic vitality.” At that time, I was not quite so contented with Gorlatch’s performances of the Chopin Etudes: “Having praised his purposefulness, it seems churlish to remark that I wish he would loosen up a bit. Playing a concert also has a side potential for entertainment, and although I certainly don’t want ‘cuteness’ and pandering to an audience, I daresay that there is room for a bit of drama and communication…Mr. Gorlatch is obviously a great talent, but as he develops, he will realize that a performer can also be communicative and be fun to listen to…’’ That was when he was 18.

I am particularly pleased to report that at this concert–four years later–he showed just the type of growth I would hope for (and expect) from an already promising artist. His performances of Beethoven’s Op. 110, Bartok’s “Out of Doors”, Four Debussy Preludes and a Chopin group had far more nuance, flexibility, color, and humor. The Beethoven sonata was notable for its almost operatic cantabile, and the pianist brought out innumerable, cherishable passing felicities. I am a bit surprised, however, that he chose to divide the runs in the first movement between the hands (as Beethoven himself calls for in the E major recapitulation later on), but this is a miniscule quibble.

The Bartok had great sensitivity and a feeling of detached understatement. The accuracy and precision were indeed awesome, although the requisite calm and repose of “The Night’s Music”’s insect noises were judiciously recreated against an unusual backdrop of anxious momentum. The opening “With Drums and Pipes” and the culminating “The Chase” were unusually subtle, but a bit too refined. Gorlatch’s way with the Bartok reminded me of Perahia’s sensitive interpretation.

One could say the same thing about the Debussy which–high praise indeed–were in the Gieseking tradition. He elicited a beguiling fragrance in “Les Sons et Parfumes Tournent dans du Soir” (from Book II) and an almost troubadour like declamation of “La Fille aux Cheveux de Lin” that made it seem it was being improvised on the spot. For once, “Feux d’Artifice” (Book ll) sounded decorative and entertaining (not the usual bombastic firecrackers that burn your hands!). “Ce qu a vu le vent d’Quest” (Book l) similarly may have been more notable for its delicacy than its Katrina-like ferocity; but its sophistication ultimately won me over.

In the concluding Chopin group, the “Barcarolle”–a bit laid-back at first–did summon a modicum of drama; the ending run was terrific. Four Mazurkas from Op. 67 and 68 were undulant and dance-like; (the A minor, Op. 68, with its trills, was played “Lento”– a slow dance, not “Lento” as a dirge); I liked its curvaceousness. The A-flat Polonaise, Op. 53, a mite small-scaled for my taste, was almost too easy for him; the famous octaves went by astonishingly and fleetly well. (But Rubinstein’s sui generis interpretation will always stubbornly retain my loyal affection).

And I am delighted to observe: Mr. Gorlatch’s new stage presence has livened up gratifying well. He gave us two encores: the c-sharp minor Etude, Op. 10, No. 4 was almost Richter-like in its brilliance and headlong tempo; and the E-flat Waltz, Op. 1 came forth with intoxicating dazzle.

A wonderful concert!

by Harris Goldsmith for New York Concert Review; New York, NY