It is a testament to the gifts of Franz Liszt that, well into this year of countless 200th anniversary commemorative concerts, Liszt’s music still emerges as the inexhaustible treasure that it is. Having given several all-Liszt recitals just a few weeks ago, I had some hesitation about this assignment to review a Liszt program, but my faith in the diverse repertoire and acceptance of a wide variety of interpretive styles won out. As it has always seemed to me more meaningful to be reviewed by musicians with genuine experience in the repertoire being performed, that belief also helped offset any reservations. After all, a pianist is often the best judge of what sets (or doesn’t set) another pianist apart.

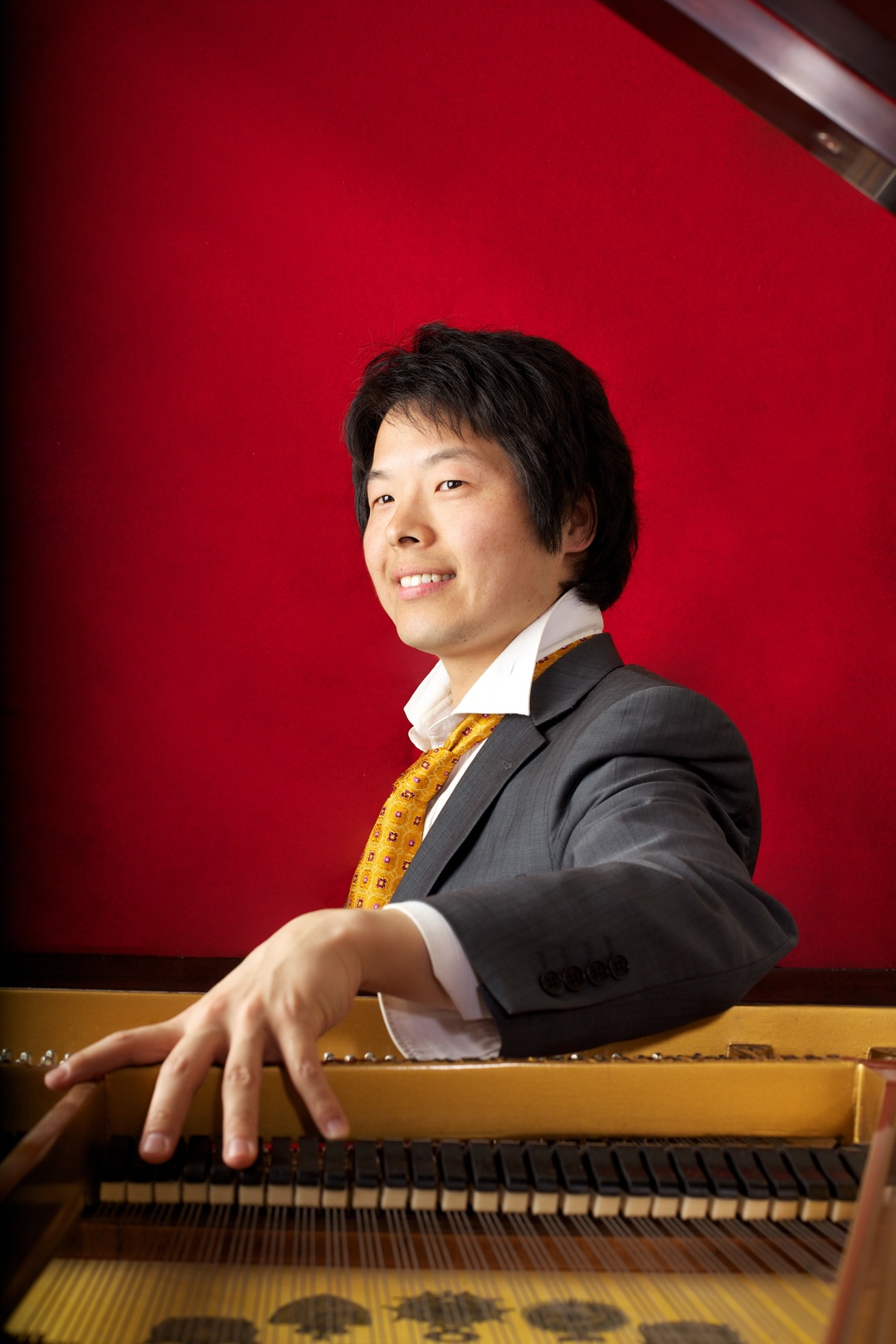

Adam Gyorgy is a young Hungarian pianist whose publicity sets him apart long before one enters the concert hall. Eye-catching photographs of the athletic Mr. Gyorgy in various exuberant action poses are matched by a biography that, in addition to the expected litany of credentials, traces his performing life to his early childhood tendency of drawing houses upside down, in consideration of the perceptions of others across a table. One imagines it was the same extroverted spirit that spurred the 2009 founding of his Adam Gyorgy Castle Academy in his native Hungary, also an effort to “give back” after all the help he received in his youth. Judging from Sunday’s performance, Mr. Gyorgy has much to give – it is only a question of how best to do it.

Starting from the high points, Gyorgy closed the evening by bringing brilliance and élan to a work that has been beset with kitschy associations for almost a century, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. While there are other works that offer a much nobler example of Liszt’s output, Gyorgy’s fresh and engaging performance dispelled preconceptions. Moving backwards from this last programmed work (in upside-down-house fashion), one enjoyed an excellent performance of Liszt’s La Campanella from the Paganini Etudes. Sure-fingered and seemingly effortless, this performance also had the greatest tonal and dynamic range of the evening. It seems Mr. Gyorgy has lived with both this Etude and the Rhapsody, and they could easily become “signature” pieces.

Preceding these last two pieces, Liszt’s Rigoletto paraphrase was delivered with polish and confidence, but it was not set apart from the standard that one has come to expect, technically and interpretively, from any number of today’s young conservatory graduates. A similar impression was left by the pianist’s straitlaced performance of Chopin’s Ballade in G minor, which also seemed somewhat anomalous on this Liszt tribute program, despite the fact that Liszt and Chopin were contemporaries.

What was more puzzling, though, was that Mr. Gyorgy chose to play the Chopin (or anything for that matter) directly after Liszt’s epic B Minor Sonata (the recital having no intermission), making the latter masterpiece somehow a mere prelude to increased brilliance. It seemed a disservice to both Chopin and Liszt to juxtapose them this way. Some pianists (perhaps those who are trying to see and hear things from a lay audience perspective – the upside-down house) find the Liszt’s quiet ending problematic and awkward, hastening to follow it with more instantly gratifying works; even an untutored audience, however, can be trusted to grasp the depth of its final utterances and savor the silence. Perhaps this is a case for building the metaphorical house from the ground up and letting the audience come inside – there is integrity in that. An intermission would have helped.

What matched the Sonata’s minimized role on the program was the understated performance itself, subdued to the point where my companion asked whether there was a problem with the piano. The work seemed never to catch fire, with climaxes in the score (some marked triple forte) emerging muffled and monochromatic. The inherent wrestling and storming in this highly dramatic work were absent, while phrases needing to be ponderous or prescient became moderate and Mendelssohnian. Having encountered literally hundreds of renditions of this work, live and recorded, I found it difficult to embrace this one. The notes were mostly there, with admirably few smudges (not exactly unusual these days), but I needed more.

The recital’s opening “Improvisation” by Mr. Gyorgy did not help set up the Liszt either. Full of repeated primary harmonies in a sedate, New Age-type style, it seemed to dull the acute type of listening that the ensuing motivically complex Sonata requires. While quite pretty and delicately shaded, it bathed one’s ears in a wash of somewhat facile diatonic “heaven” that rendered almost meaningless the hard-won apotheosis of Liszt’s thirty minutes of high Romantic grappling. All in all, I will be eager to hear Mr. Gyorgy’s very promising playing again, but hopefully with more effective programming and more personally compatible repertoire choices.

An encore of the Liszt-Mendelssohn Wedding March (not the popular Horowitz version, but an extended transcription seeming to borrow from it) concluded the concert with spirit and humor.