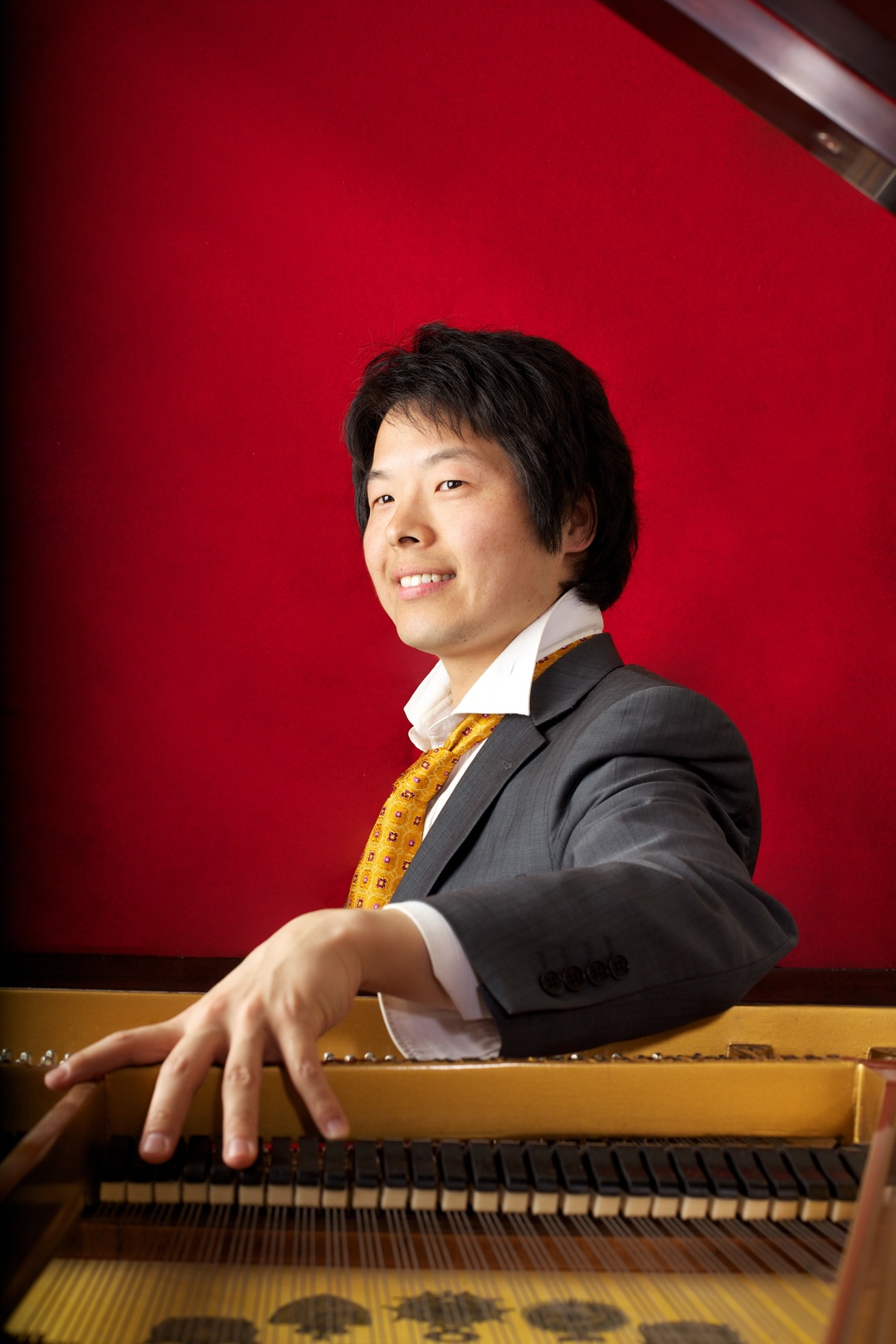

MidAmerica Productions has a long history of presenting talented artists in venues around the globe. The honor of the 1200th concert worldwide was given to the Brazilian pianist Aleyson Scopel in a program featuring Mozart, Schubert, and his countryman, Almeida Prado. Mr. Scopel dedicated his performance “To Alys Terrien-Queen, the first to believe in me.” Terrien-Queen may have been the first believer, but after this performance, he added countless others, including this listener, as those “in the know.”

Opening with Mozart’s Rondo in A minor, K. 511, Mr. Scopel demonstrated his mature understanding of this highly introspective and melancholy work. He played with refinement and sensitivity, but without superficiality or glibness that lesser players sometimes display in Mozart. His control was excellent, the voicing clear, and contrasts rendered decisively. His was the playing of an artist, pure and simple.

The world premiere of Cartes Celestes XV (Celestial Charts XV) by Almeida Prado followed the Mozart. José Antônio Rezende de Almeida Prado (1943-2010) composed eighteen sets of pieces he called Cartes Celestes , works depicting the sky and universe, using a harmonic language the composer called “transtonality.” Cartes Celestes XV was finished in 2009 and dedicated to Aleyson Scopel. Subtitled “The Expanding Universe”, it is divided into six movements. The opening GRB090423, a musical depiction of a supernova 13 billion light years from the earth, was played by Mr. Scopel with harrowing effect, from the rumbling of the unstable stars to the brilliant explosion of light. The other movements (Eskimo Nebula, Pictor Constellation and Extrasolar Planet, The Bird of Paradise Constellation, Planetary Nebula NCG 3195, and Solar Wind) were further examples of the genius of this composer and his visionary conceptions. Almeida Prado pays tribute to his teacher Messiaen in Bird of Paradise. One can also detect some intergalactic Debussy (imagine La cathédrale engloutie in outer space!). The use of tonality without a tonal center, which the composer called his “pilgrim harmony”, was highly effective. Mr. Scopel took the listener on a tour of the stars in a spellbinding performance full of power, passion, and lyricism. After he had finished, Mr Scopel pointed to the sky in tribute to the composer. It was a touching gesture, and I am confident that Almeida Prado was listening with joy from somewhere in the vast universe he loved so much. Given that Mr. Scopel has recorded other of the Cartas Celestes, it is a reasonable hope that he will, at the very least, add this set to the mix, but I would very much like to see him record all eighteen Cartas Celestes. It would do honor to both Mr. Scopel and Almeida Prado.

After intermission, Mr. Scopel offered Schubert’s Sonata in A major, D. 959. This Sonata, completed only months before Schubert’s death, is a monumental work that is majestic, pathos filled, and nostalgic (especially in the finale’s look back to a theme from his Sonata in A minor, D. 537). Mr. Scopel continued to share his artistry with a well-considered and executed performance of this massive work. His playing was crisp and accurate. The contrasting moods were dynamically realized, the laments were moving in their simplicity, and the finale had unflagging energy. One must also contend with the virtuosic elements throughout, and Mr. Scopel was more than capable of dealing with those as well, which he did in an unpretentious and understated way. This was fine Schubert playing, and would have served as an excellent example to students on what constitutes a reference performance.

Aleyson Scopel is a first-rate pianist. Anyone who values substance over style should make it a point to hear him in performance. I look forward to hearing him again.